The Electricity Buzzar

Background

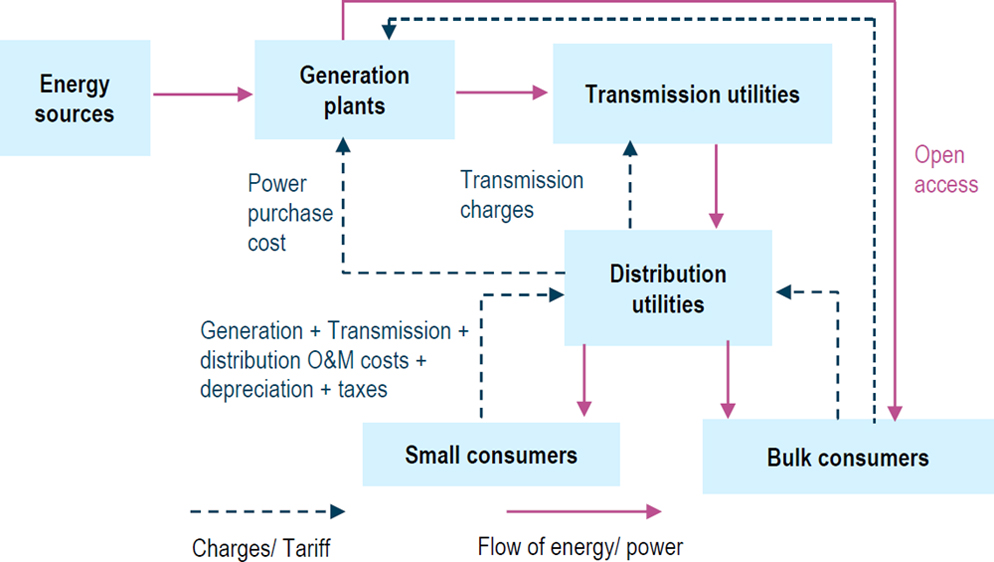

The power sector consists of five stakeholders- energy sources, power generators, transmitters, distributors, and consumers (figure 1). The draft National Electricity Plan 2016 projects that the peak demand at the end of 2021-22 would be 235 GW.1 As per the 2019 CRISIL report, India’s installed capacity of power generation is 344 GW. Produced electricity could only be transported to the region of demand if the transmission network is capable. The current transmission line capacity in India is 3.9 Lac km. It grew at a compound annual growth rate of 7.2% from 2012 to 2018.

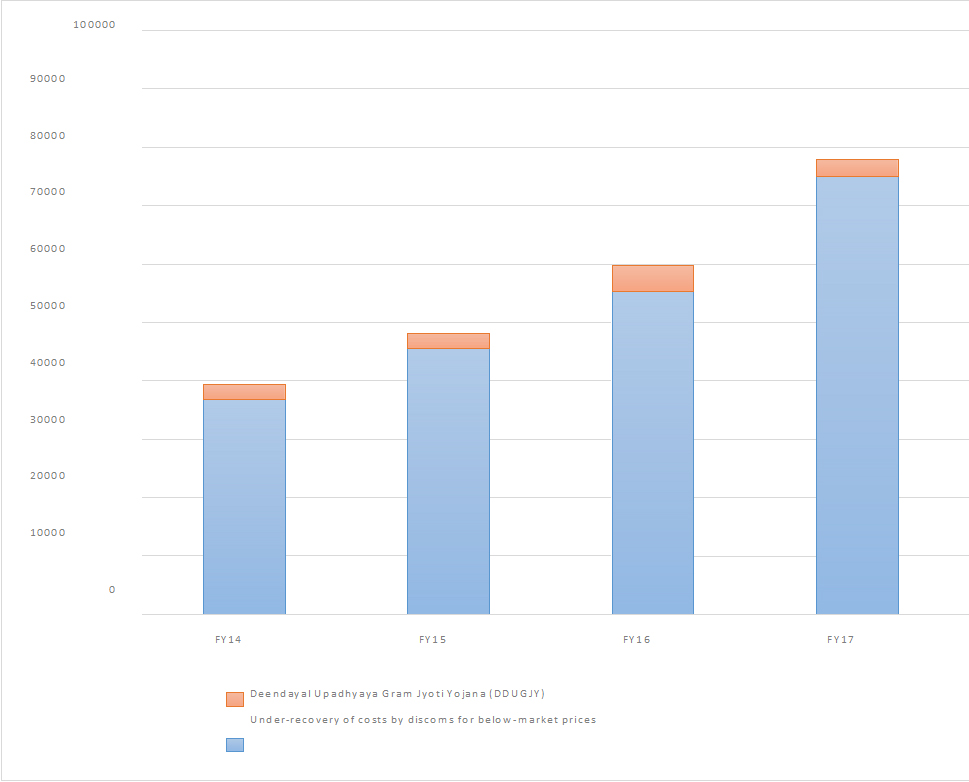

The power generation capacity is sufficient, and the transmission capacity is rapidly growing, but the power distribution is the weakest link in the value chain. Since 1991, the power sector has seen several reforms to improve the status quo, but they failed to address the issue of the DISCOMs being in perpetual losses. The fundamental issue is that DISCOMs fund their operational losses by debt. As of March 2015, the state DISCOMs had accumulated outstanding debt of approximately ₹4.3 lakh crore and roughly ₹3.8 lakh crore losses.2 The government launched UDAY (Ujjwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana) to allow the states to help DISCOMs overcome these losses. The scheme helped the DISCOMs clear their books, but it did not resolve the loss accumulation’s fundamental issue. DISCOMs are in losses because of a substantial mismatch between fixed cost and the recovered fixed charges. The mismatch reflects due to the electricity consumption subsidy and the Aggregate Technical and Commercial (AT&C) losses. Electricity consumption subsidy is the largest share (49%) in India’s pie of total energy subsidies. In the financial year 2017-18, the total electricity consumption subsidy was ₹86400 crores.3

The government subsidizes electricity for some consumers, such as metro rails, railways, and agriculture consumers. DISCOMs provide subsidized electricity to these consumers and get compensated by the government later. However, governments tend to delay payments, which creates a non-recovery of the fixed utility costs.

The central and state regulators (CERC and SERC) and the DISCOMs recover these ‘losses due to subsidies’ by cross-subsidizing the low-tariff users by increasing the variable charge of the high-tariff users. This practice increases the cost of electricity.

What is the fixed and variable charge?

The supply tariff (payable by the consumer) is divided into two categories: fixed charge and the variable charge. When the consumer books a connection, the DISCOM sanctions a specific load to that consumer. The fixed charge corresponds to that sanctioned load. Variable charge corresponds to the actual consumption of the consumer.

The fixed charge includes capacity charges payable to power generators, transmission charges, operation and maintenance expenses, depreciation, interest on loans, and equity return. The variable charge recovers the variable utility costs, such as the variable cost component of power purchase.

Looking at the power sector from the first principles

According to Shah and Kelkar, the state is an inefficient institution. They establish the fact by giving a law of unintended consequence, which causes the state inefficiency- “”A government intervention that carries an intention to have a certain outcome will very often end up yielding a very different result.””4 Market freedom works well in producing goods and services efficiently. The state should intervene where the market fails to provide efficiency. The market fails when there is information asymmetry between the producer and the buyer, a monopoly in the market, any externality (non-negotiated outcomes) involved, or in the case of public good.5

An individual can be prohibited from consuming electricity (excludable), and its consumption by an individual affects the overall supply (rival). Since the production, transmission, and distribution of electricity are excludable and rival, therefore principally it should be produced, transmitted, and distributed by the market, i.e., the private players. There is no state intervention required until a market failure could be quantified in terms of externality (positive and negative), market monopoly by a private player, information asymmetry, and public good.

With the electricity act of 2003, the government tried to create a free market in the power sector. The intention was to harness market efficiency in the sector by inviting private players to create competition, negotiation, and choice. As per the power sector’s status quo, the government-owned utilities generate 54% of the total power. 92% of the transmission utilities are government-owned, and the government owns almost all the DISCOMs (distribution companies) except in Delhi, Mumbai, and in a few other cities.5 Hence the government did not succeed in their original intention.

For a free market to function, price control by the government distorts the supply and demand equilibrium as it creates a deadweight loss6 to the economy. A free market does not keep entry barriers, and the market mechanism decides the profit margins.

Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) and State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC) regulates the tariffs of DISCOMs heavily. As per section 79 and section 86 of the electricity act 2003, CERC and SERC control the tariffs of the generation, transmission, and distribution companies and issue licenses for the market entry, fix trading margins, and specify the grid technology, and adjudicate upon the disputes.7

The case of state intervention in the power sector

Let us consider that there is no state. The market will have the responsibility to produce, transmit, and distribute the electricity. The state will then intervene through either financing or regulating the market. It should not produce because, in this sector, there is no public good. There are four possible market failures

1. Negative Externality: 64% of the electricity production in India is by coal-based thermal power plants (Source: Ministry of Power; PRS). The production of electricity by coal-based thermal power plants requires coal burning, which pollutes the air. Air pollution is a negative externality because there is a channel of influence between the polluter and the citizens that are not negotiated.

Since it is a market failure, the state should intervene. There are two modes of intervention that seems possible in this case:

a. Regulation and Tax mechanism: States can regulate the thermal power plants by putting stringent emission norms and imposing taxes on the plants’ amount of pollution. The tax may act as a disincentive to the polluters, and they will pollute less.

b. Create a pollution market: The state can limit the aggregate pollution that all the thermal plants can cumulatively make and make the emission tradable.

To understand the two interventions and their efficiency, let us create an oversimplified hypothetical scenario to understand the market mechanism. There are two power plants X and Y, with a production capacity of 2GW per year. Plant X pollutes 4 million tonnes of CO2 for the 2GW production, and plant Y pollutes 5.33 million tonnes of CO2 for the same production. A plant can earn $100 per GW per year. To safeguard the broader public health and reduce the pollution levels, the state put a ceiling on the amount of CO2 that a power plant can emit. As per the norms, a plant with a 2GW capacity can pollute up to 3 million tonnes per year. Under this regulation, the total power generation in the society would be 2.62GW (X=1.5GW and Y=1.12GW), assuming the proportional relation between emission and power produced. If the cost of pollution to society is $30 per million tonnes, then the overall capital generation would be $82 (X: $150-$90 and Y: $112-$90). The $30 will be charged from the power plants as the carbon tax.

Bringing the market mechanism (Concept of carbon trading): In our oversimplified hypothetical scenario, let us bring the market mechanism and analyze the results. Instead of a simple regulation-tax mechanism, the state decides to sell the total emission quota. The cost of 1 million tonnes is $30. Plant X a and Y bought their quota of 3 million tonnes each for $90. Plant Y knows that plant X has a capacity of 2GW. Hence it is in its interest to sell the quota of 1 million tonnes to plant X. After the trade, plant X will operate at its full capacity and over-pollute, whereas plant Y will under-pollute. The overall pollution will remain at 6 million tonnes. However, the overall capita generation in society would be $95 with the production of 2.75GW.

Tax collection is a costly affair. Tax collection is costly, therefore spending one rupee of the tax money is equivalent to spending three rupees.8 Even if $30 is charged as tax from each plant in the first method, the net value of the tax collected would be one-third of the total, i.e., $10 only. In the method of carbon trading, this inefficiency is also removed.

2. Positive Externality: When the supply and demand are met, the market reaches an equilibrium price. However, there will still be a marginalized population left that will not be able to afford the electricity at the equilibrium price. Hence either there is less consumption or no consumption. The electricity consumption is directly proportional to the GDP. Access to power increases the overall production, nudges small scale manufacturers to enter the market, boosts the retail market of electrical appliances, and increases the standard of living. Hence there is a case of a positive externality.

Currently, the government provides subsidy and regulates supply tariff structure. This subsidy and regulation model creates complexity in tariff structures that lead to information asymmetry and decreases the overall efficiency of benefits. Instead, it should use the method of direct benefit transfers to promote consumption. It is a low cost and a less intrusive method.

3. Information Asymmetry: In a free market, the power demand fluctuates frequently. The demand fluctuation depends on various factors like peak hours and seasons. Depending upon the fluctuating demand, market prices could vary. If there is a lack of transparency in these fluctuating prices, the DISCOMs may hide the information and overcharge the consumer. Without information about the price fluctuation in the public domain, the consumer will not know if the DISCOMs are overcharging it.

The government should intervene and monitor the market and make the information available in the public domain so that the consumer could decide to continue with the present service provider or move to another service provider.

4. Monopoly: The distribution business is the combination of content (electricity) and carriage (wires). A distribution company owns the wires in an area and supplies electricity purchased from the producer and drawn from the transmission. Such ownership of wires makes the DISCOM a monopoly in that area. As per the Electricity Act 2003, the consumer can choose a different DISCOM for the electricity supply. If the current DISCOM owns the wires, it will always overcharge the other DISCOM for using the wires. This capability-to-overcharge will give an edge to the wire owner to interfere in the pricing of its competitors. This edge will make the current service provider a monopoly. DISCOMs also tend to pose operational barriers and procedural delays/rejections when switching to other providers on unreasonable grounds.

A study commissioned by the Forum of Regulators in 2015 suggested the separation of content and carriage (C&C). Such separation will make the carriage a separate entity that can provide services to any DISCOM. The wire company will not get involved in the content business. This separation will rule out any possibility of a monopoly creation.

Stakeholders respond to the incentives in a free market. Individuals running the state-owned utilities behave in their best interest. The incentive for a government employee, in this case, is not to optimize the process to compete in the market as there is less and unfair competition. Moreover, substantial political intervention weakens the market further.

In a free market of private players, the incentive structure changes, and it brings competition and efficiency in the market. Below is the predicted incentive structure in the power market that is free and has minimum state intervention.

| Stakeholders | Incentive | Expected action in a competitive market |

| Producer | Produce up to its optimal capacity to maximize their profits. | Maintain the demand by keeping the prices low and increase efficiency to compete in the market. |

| Transmission | Win more transmission contracts to survive the market. | Keep transmission losses low and maintain the high capacity to maintain low transmission cost. |

| DISCOM | Maximize the consumption of consumers and win more customers | Reduce outage by investing in technology like smart metering to monitor real-time consumption data. Minimize the tariffs to increase demand and consumption. |

Atma-Nirbhar Package

Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the Atma Nirbhar package on May 12. It was indicated that this special economic package would be worth 20 lakh crores, which is approximately equal to 10% of the country’s GDP. The Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, in her subsequent conferences, unfolded the specifics of the interventions that the government is planning out of the relief package.

In the power sector, DISCOMs were given special attention, and the following interventions were announced:

1. Intervention: At present, the consumer bears the cost of the inefficiencies in various processes by the DISCOMS. However, as per the announcements, the DISCOMS would have to bear the cost of their inefficiencies. The government may come up with some penalty system for the DISCOMS for the inefficiencies such as load-shedding.8

This could prove as a needed intervention in the market. This is because due to these regulations, the DISCOMS would be disincentivized to use inefficient ways of distributions.

2. Intervention: The government has planned to remove the regulatory asset funds that were provided to the distribution companies.

3. Intervention: It is planned that the distribution companies would be provided the monetary support (liquid) of approximately 90,000 crores. This extra support is given so that the distribution companies could be relieved from the power GENCOS’s liabilities.

This could be a short-term plan but would remain ineffective. Earlier, the government has tried many times to de-burden the DISCOMs but failed in the longer run. This is because we need to develop more freedom in the sector and inscribe it in the Electricity Act 2003.

4. Intervention: The government has decided to privatize the distribution companies in the union territories.

This intervention is needed but not sufficient. Privatization brings market freedom. Even the Electricity Act of 2003 proposes an open market competition. Still, we see that the market mechanism is not functioning as per its full potential. Removing the government’s market monopoly in the market economy is essential, but still, there is a chance of the creation of other kinds of monopolies due to the non-separation of carriers and content. Hence there could be two ways forward:

a. The carrier and content entities should be distinct and different in the power distribution market.

b. The privatization of DISCOMs must be done in all states.

Conclusion

Electricity to the country is like blood to the body. The more efficiently it circulates, more will be the growth of the economy. Unfortunately, the circulation system of electricity is cluttered. India claims to have achieved 100%9 electrification that provides the necessary infrastructure for electricity reach in the country’s remotest part. With the installed capacity of 324GW and demand of the only 270GW, India sits on a surplus production capacity of 54GW per year.

Nevertheless, we have power outages, and DISCOMs are in loss. 17 years ago, the country opened her market for competition, but still, we have a government monopoly in production, transmission, and distribution of the power sector. With the non-alignment of incentives and open yet restricted private players’ entry, the current power structure will continue to disappoint. Even after 73 years of independence and 17 years of significant policy reforms in the sector, many see electricity as a rare and expensive commodity.

The power sector is like a broken machine, and the reforms are acting like a repair or replacement of a broken part. We need to change the entire machine. John Maynard Keynes said that “”The important thing for government is not to things which individuals are doing already, and do them a little better or a little worse, but to those things which at present are not done at all.”” State intervention is justified only in the zone of market failures. The state should not get involved in either production, transmission, or distribution of power. The first policy problem is to establish a system where the market can work with freedom. The second policy problem would be market failures. The state has a huge role to play in the market failures in the power sector. It must remove the externalities by regulating the market and giving the freedom for carbon trading to prosper. Removing information asymmetry and breaking monopolies will increase efficiency and produce more utility for society.

References

- CRISIL Infrastructure Advisory. (2019). Diagnostic study of the power distribution sector. Niti Aayog, Government of India. http://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-08/Final%20Report%20of%20the%20Research%20Study%20on%20Diagnostic%20Study%20for%20power%20Distribution_CRISIL_Mumbai.pdf

- UDAY (Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana). (2015, November 5). Financial Turnaround of Power Distribution Companies. Press Information Bureau, Government of India. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=130262

- Soman, A. (2018). India’s Energy Transition: Subsidies for Fossil Fuels and Renewable Energy. International Institute for Sustainable Development. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/india-energy-transition-2018update.pdf

- Kelkar, V., & Shah, A. (2019). In Service of the Republic. Penguin Random House India. https://penguin.co.in/book/uncategorized/in-service-of-the-republic/

- Mishra, P. (2012, 9). OVERVIEW OF THE POWER SECTOR. PRS Legislative Research. https://www.prsindia.org/sites/default/files/parliament_or_policy_pdfs/Overview_of_the_Power_Sector_final_web.pdf

- Samuelson, P. A. (n.d.). Economics (19th ed.). McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. (2003, June 2). The Electricity Act, 2003 [No.36 of 2003]. Cercind. http://www.cercind.gov.in/act-with-amendment.pdf

- Kumar, A. (2020, May 20). Summary of announcements: Aatma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan. PRS Committee Reports. https://www.prsindia.org/report-summaries/summary-announcements-aatma-nirbhar-bharat-abhiyaan

- Choudhary, A. (2018, November 13). Modi’s village electrification is among world’s biggest successes this year, says this report. The Financial Express. https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/modis-village-electrification-is-among-worlds-biggest-successes-this-year-says-this-report/1380269/

The views expressed in the post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the ISPP Policy Review or the Indian School of Public Policy. Images via open source.

Shashank Mishra

Shashank Mishra is the co-founder of Samavesh, a digital platform that enables constructive policy discourse in civil society. He cherishes long conversations over tea. His work experience in the not-for-profit, government consultation, startup ventures, academia, and corporate sector enables him to bring first-hand perspectives of various social actors into policy discussions. He is an alumnus of the Indian School of Public Policy. He loves performing theatre, poetry, sketching, and, not to mention, conversations.