Table of Contents

Tariff Policy: US should prioritise economics over politics

President Donald Trump’s current tariff policy for India and other developing nations compels one to think that he wants to rewrite history. But it will be a failed history, if he does not retract from current rates of imposition, which is as high as 50% for India and Brazil.

Simply, because each country exports products where it enjoys an advantage and imports products where it has disadvantage. Besides, any tariff imposition should be backed by economic rationale or empirical findings, and the theory of protecting domestic industries at the cost of exports is bygone.

David Ricardo’s free trade theory

Free international trade was even advocated by classical economist David Ricardo. His theory of free international trade centres around the concept of comparative advantage, which specifies that countries benefit from specializing in goods they can produce at lower opportunity cost (the value of the next best alternative foregone) and trade them with other countries. Ricardo’s theory was a challenge to mercantilism and protectionism, advocating for the reduction or elimination of trade barriers like tariffs.

His theory posits that it is comparative advantage against absolute advantage (producing all goods using fewer resources), which leads to increased overall global production and consumption.

Contemporary postulates

Modern day economists such as Stephen Cohen have stated that the theories of comparative advantage (both classical and neoclassical) imply that liberalizing trade is beneficial to consumers in any country. As increased competition from trade liberalization will lead to lower prices by the domestic firms and thus bring in efficiency. The resultant consumer’s savings can be spent consuming other products.

The UNCTAD’s (UN Trade & Development) Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) is based on Ricardian trade theory suggesting patterns of trade among countries are governed by their relative differences in productivity (Data Centre). Its RCA metric calculator for different country uses trade data that “reveal” such differences. The metric can be used to provide an approximation of a country’s competitive export strengths. However, national measures which affect competitiveness such as tariffs, non-tariff measures, subsidies, etc are not considered in the RCA metric.

The SITC (Standard International Trade Classification) code, which categorizes traded goods (with codes ranging from a broad section to more specific levels for various products) have been referred to using data from the trade matrix available in UNCTAD Data Centre.

The RCA metric is calculated using a mathematical formula. A particular country is said to have a revealed comparative advantage in a given product, say, i when its ratio of exports of product i to its total exports of all products exceeds the same ratio for the world as a whole.

When a country has RCA >1 for a given product, it can be inferred that it is a competitive producer and exporter of that particular product against a country producing and exporting that good at or below the world average. The higher the value of a country’s RCA for product i, the higher is its export competitiveness in product i.

Using this metric the relative competitive strength of different countries, be it the USA, Russia, Brazil or India can be ascertained for different products from food and live animals, beverages and tobacco, manufactured goods to mineral fuels.

In sum, from classical to neo classical to modern day economists, all used well derived methodologies to analyse export competitiveness and most discarded trade barriers like tariff.

India, Brazil, China, Mexico and Vietnam have been levied with 50, 50, 30, 25 and 20 percent tariffs respectively by the US. In the era of multilateral rounds of trade negotiations, regional blocks and bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs), parties are reducing or/and eliminating tariffs on trade. Trump’s tariff policies hold no water.

Public policy implications

While tariffs are typically discussed in economic terms, they also carry significant public policy implications. They are not just numbers on trade sheets rather are being used to send signals, to pressure, and sometimes to threaten.

US’ own public policy experts are pointing that out. Jeffrey Sachs an American economist and public policy analyst who is a professor at Columbia University, has suggested that India focuses on other trading partners like BRICS emerging economies and considers joining regional trade blocs like RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership).

In a recent media interview to India Today Sach said, that United States is shortsighted, poorly led, unstable and not the basis for India’s long-term development.

Anup Wadhawan, former Commerce Secretary at Government of India and Senior Fellow at ISPP is of the view that the Indian experience with the opening up in 1991 and FTAs with South Asian neighbours, ASEAN, Japan, South Korea, and the UK reflects that openness leads to net overall gains. We are undoubtedly better off today in terms of overall economic and external sector strength than in 1991. He adds, “gains from trade are shared with trading partners in proportion to relative competitiveness. He further explains that beyond moderate levels, tariffs, at best should be short term measures for very pointedly regulating certain aspects of cross-border economic activity on prudent policy considerations.

Austan Goolsbee, President of the Chicago Fed, described Trump-era tariffs as a “stagflationary shock”—a rare and dangerous combination of high inflation and stagnant economic growth. This double-hit-tariffs increase prices while reducing trade, investment, and growth-is self-defeating. Goolsbee warns they resemble past stagflationary crises like the 1970s oil shocks.

Influenced tariffs

When the United States warned India of higher tariffs if it continued to buy oil from Russia, it was less about trade and more about influence. India did not give in. Part of that can be said to be simple calculation from a game theory perspective; India could assess whether the U.S. would actually follow through on its commitments. Here comes the concept of ‘credible threats’. If the U.S. raised tariffs too high, it would hurt its own importers and consumers. Knowing this, India has done its own calculations.

Quantitative models demonstrate that tariffs lead to a decline in consumer surplus, with the difference between pre-tariff and post-tariff consumer welfare creating substantial net losses much in line with the classical economic theory that tariffs create deadweight losses by distorting market prices away from their efficient equilibrium.

Contrary to Trump’s stated goal of protecting American manufacturing, empirical evidence also shows us that tariffs often harm more manufacturing jobs than they create. On a closer look at Trump’s 2018 tariffs, The Federal Reserve Board study by Aaron Flaaen and Justin Pierce found that by mid-2019, increased steel and aluminium costs due to tariffs were also associated with relative reductions in manufacturing employment. This validates Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage in practice – when governments artificially protect one sector through tariffs, they harm other sectors that depend on those inputs, creating a net negative effect on industrial employment.

In response to Trump’s 50% tariffs on Indian exports, the India government is bringing out a comprehensive support package for exporters. However, it needs to be watched if by doing so the government does not compromise its spending on its welfare schemes.

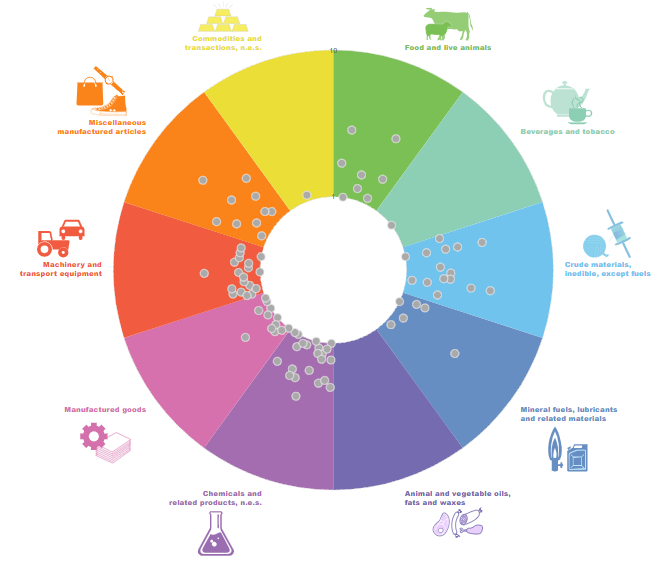

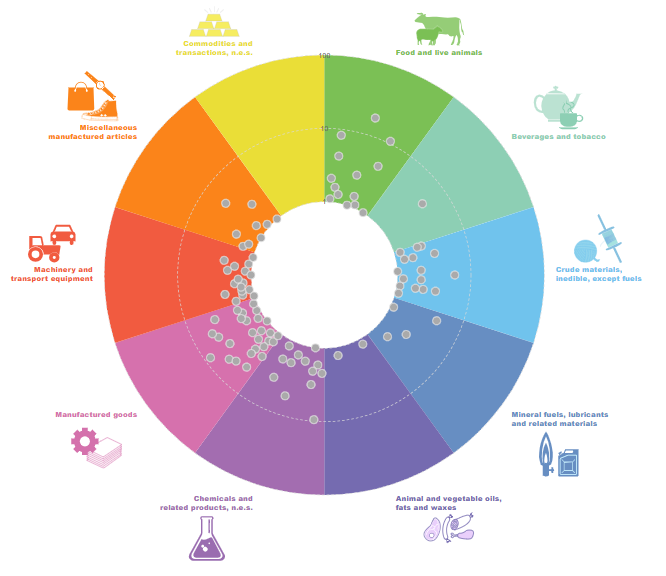

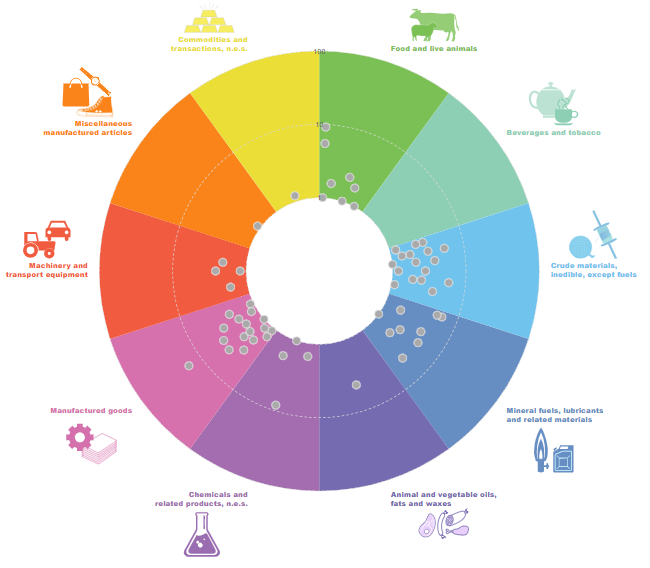

Revealed comparative advantage plot

The charts below show various sectors of the economy, according to the SITC classification for the US, India and Russia. The revealed comparative advantage of exported products are given in the plot for all product groups which have an RCA greater than 1 for each of the three countries.

United State:

Image Source: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/RcaRadar.html

India:

Image Source: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/RcaRadar.html

Russia:

Image Source: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/RcaRadar.html